Senior patent attorneys know that great patent drafting requires more than strong technical writing—it requires understanding how an examiner will interpret, classify, and ultimately decide the application. Yet few practitioners ever see the inner workings of the USPTO from the inside.

In a recent episode of IP Innovators, Finnegan Partner and Head of Patent Office Practice Aaron Capron shared rare, practical insight from his years as a USPTO examiner and from his current work managing hundreds of patent families spanning AI, quantum computing, semiconductors, and neural network hardware. His reflections reveal what many practitioners intuit but few articulate: the best patent drafting today requires examiner-like reasoning, especially as AI-era inventions become more complex.

Below, we break down the most actionable insights from the episode and pair them with current best practices for high-tech prosecution.

1. How Examiners Classify Patents Is One of the Biggest Predictors of Prosecution Outcomes

One of Capron’s most revealing comments concerns classification—the step that often determines which art unit will review your case and how challenging the prosecution will be.

As he explains, a major part of what he carried from the USPTO into private practice is understanding “how they classify patents, how they move cases around…some of the internal discussions regarding some considerations.”

Classification is not a clerical afterthought. It directly shapes:

- Time to first action: USPTO data show pendency varies sharply by tech area, with software-heavy units often at the longest end of the 22+ month average.

- Likelihood of a §101 rejection: Software and business-method–oriented art units (2100/3600) routinely post §101 rejection rates between 70–90%.

- Technical depth of the assigned examiner: Hardware-focused centers like TC 2800, home to semiconductors and circuits, maintain some of the highest allowance rates and more technically specialized examiners.

- Consistency across related applications: Even one misclassified case can fracture a family’s prosecution path, especially when managing 500 families at a time, as Capron does.

For hybrid inventions—AI and chips, AI and medical devices, quantum and software—small shifts in claim language can push an application into entirely different examination worlds. And in those worlds, the odds change fast.

Practical Takeaways

Capron’s examiner-side perspective makes one thing clear: classification isn’t something you react to after filing—it's something you shape before the examiner ever sees your application. The drafting stage is your only real opportunity to influence where the case lands.

- Write the first independent claim with classification in mind

- Choose the axis of novelty that best aligns with the intended technical domain

- Use the specification’s first paragraph to anchor the invention clearly in the correct class

- Avoid presenting the invention as “software-only” unless absolutely necessary

- Hardware-anchored filings receive more predictable routing

When drafting becomes classification-aware, you’re not just preparing a better application—you’re engineering the examination environment your case will face.

2. Clear Mapping Wins In and Out of the Office

Capron describes examiner reasoning with the kind of precision that only comes from sitting on the other side of the table. As he puts it, “You got to see what arguments worked on you, what arguments you worked on your primary…As an attorney on the other side, you can apply that accordingly.”

The message is unmistakable: examiners respond to clean, direct mapping—not narrative detours.

This matters even more today, where AI and ML filings often involve dense systems: multi-stage model architectures, neural network accelerators, data-pipeline logic, and distributed compute flows.

When claims don’t track directly onto the examiner’s mental model of the invention, the result is predictable:

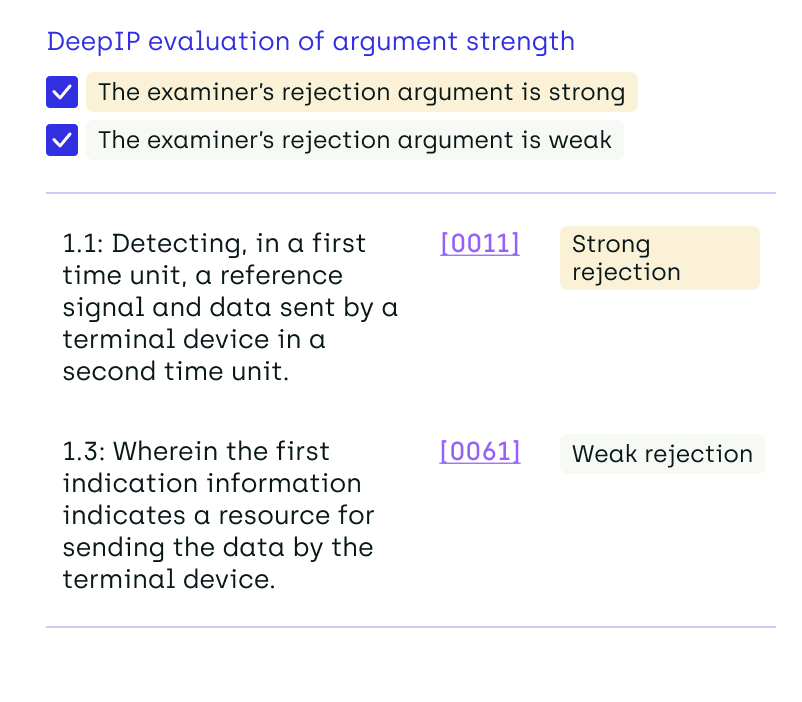

- Mismatched prior art: Under the USPTO’s Broadest Reasonable Interpretation (BRI) standard, ambiguous claim language forces examiners to interpret terms more broadly—expanding the scope of relevant prior art.

- Broader rejections: PTAB appeal statistics show that cases hinging on unclear claim construction are far more likely to end in full affirmances of examiner rejections—meaning the examiner’s broad interpretation stands.

- Repeated clarifications: USPTO prosecution statistics show that applications requiring multiple RCEs experience markedly lower allowance probability and extended pendency.

- Examiner frustration: Capron saw firsthand how ambiguity stalls prosecution long before substantive issues are resolved.

Practical Takeaways

Capron’s experience makes the examiner’s expectation unmistakable: they follow the logic you give them—so long as you give it to them cleanly. When the claim language, definitions, and arguments line up, examiners stay anchored; when they don’t, the review widens and the rejections follow.

- Synchronize definitions between the claims and the spec

- Use consistent terminology, not synonyms

- Respond with one dominant theory of patentability. Multiple alternatives weaken credibility

Clarity isn’t a cosmetic preference—it is the mechanism that determines how narrowly or broadly your invention is read, and ultimately, whether the examination stays on track.

3. At Scale, Examiner-Side Risks Multiply Fast

Capron’s examiner experience doesn’t just shape how he drafts—it shapes how he manages modern portfolios. Today, he oversees volumes few practitioners ever see: “For one client, there's probably like 500 families. For another client, there's probably 600 families.”

At that scale, the examiner-facing issues he described earlier—classification, mapping, consistency—become structural risks. Even small discrepancies can ripple across dozens of related applications.

Common failure points include:

- Missed dependencies across related families: Can trigger inconsistent examiner interpretations

- Diverging claim terminology: Amplify BRI issues when different examiners read the same invention differently

- Inconsistent §112 support: Particularly dangerous in AI filings where terminology evolves rapidly

- Contradictory arguments: Examiners flag quickly when cases share priority or subject matter

- Overextended continuation chains: Risk classification drift into less favorable art units

Capron’s vantage point makes the pattern clear: the risks examiners struggle with on a single case can scale exponentially across the entire portfolio.

Practical Takeaways

Capron’s transition from USPTO examiner to managing hundreds of patent families makes the pattern unmistakable: the same inconsistencies that frustrate examiners in a single case can quietly destabilize an entire portfolio when repeated at scale. Avoiding that drift requires infrastructure, not improvisation.

To keep examiners aligned—and to avoid the inconsistency traps Capron learned firsthand—large, fast-moving portfolios increasingly depend on:

- Consistent terminology management across families

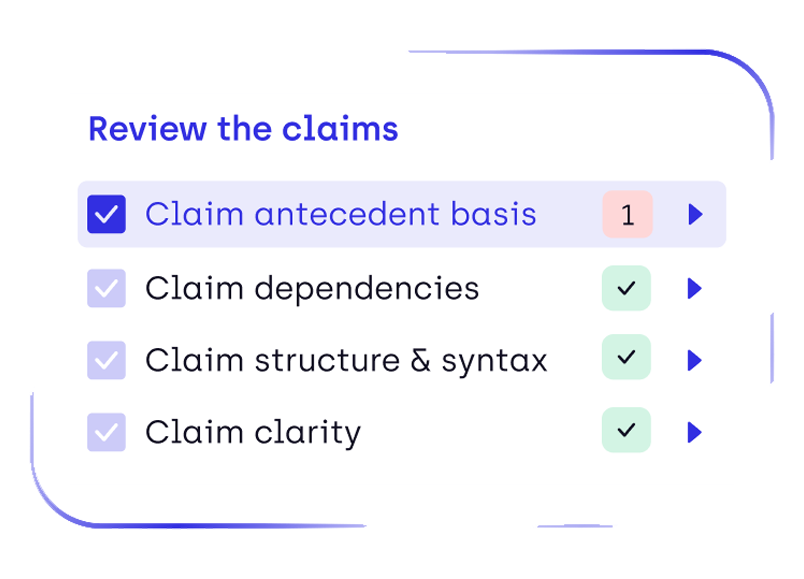

- Automated claim comparison and spec-diff checks

- Centralized office-action analytics to catch argument conflicts early

- Systematized drafting logic that reflects examiner behavior and art-unit tendencies

The lesson isn’t that large portfolios are harder—it’s that examiner-side clarity becomes exponentially more important as portfolios grow, and the teams that systematize it early gain the advantage.

4. LegalTech Requires Governance, Not Tool-Churn

Capron offers a refreshingly grounded view of LegalTech adoption. Unlike many voices in the AI conversation, he doesn’t romanticize software. He describes it the way examiners experience unclear applications, as systems that break when the inputs do.

And the sharper warning: “Sometimes, folks think that there's a problem with one piece of software and want to navigate and try something else. But anytime you do that, you're going to identify additional issues and have to go through the same thing all over again.”

In patent practice, that churn is uniquely dangerous because it breaks the very dependencies examiners rely on: consistency, stability, and predictable logic.

- Training and context are lost: AI models adapt to team style over time—resetting breaks that learning curve

- Terminology consistency resets: A critical issue when examiners evaluate wording under BRI

- Argument logic diverges across tools: May lead to downstream contradictions across families and continuations

- Data governance fragments: Risky for confidential claim sets and enablement details

- Time-to-adoption never compounds into ROI: Each switch restarts the proficiency curve

Capron’s point mirrors his examiner experience: systems fail when they lack structure. Just as inconsistent claim language triggers broader interpretations, inconsistent tooling triggers operational drift.

Practical Takeaways

Capron’s warning about tool-churn points to a simple operational truth: legal tech only becomes reliable when it’s embedded in a stable, repeatable system. Teams that jump between platforms never reach the maturity where the software—and the people using it—actually improve.

- Adopt one core drafting/analysis platform and reinforce it with process

- Build human review layers instead of switching tools at the first failure

- Log recurring issues and integrate them into team workflows

- Treat AI patent drafting tools as long-term infrastructure, not experiments

In other words, Capron’s advice echoes what seasoned patent teams already know: AI doesn’t replace processes—it amplifies them.

Invest in the system, not the swap.

5. The Real Future Skill: Staying Technically Current—Because Examiners Can’t Keep Up for You

“You have to stay up-to-date on this stuff. That's the part that's intriguing.”

Coming from a former examiner, this isn’t casual advice—it’s a reminder that the USPTO cannot update as fast as the technologies it evaluates. Examiners work within rigid classification structures, often years behind emerging fields like neural network hardware, AI accelerators, quantum architectures, and hybrid medical/AI systems.

When the technology moves on 6-12 month cycles but the Office moves on multi-year norms, the burden shifts to the practitioner.

As Capron’s earlier comments about classification hint, examiners struggle when:

- Prior art becomes obsolete faster than the MPEP evolves

- Inventions iterate more quickly than continuation strategies can stabilize

- Claim frameworks drift because the underlying technology has shifted

- New architectures don’t fit existing art units, leading to inconsistent routing or inappropriate analogies to older tech

In this environment, staying technically current is not a bonus skill—it’s the only way to draft applications examiners can meaningfully review.

Practical Takeaways

Capron’s examiner-informed lens translates into clear operational needs:

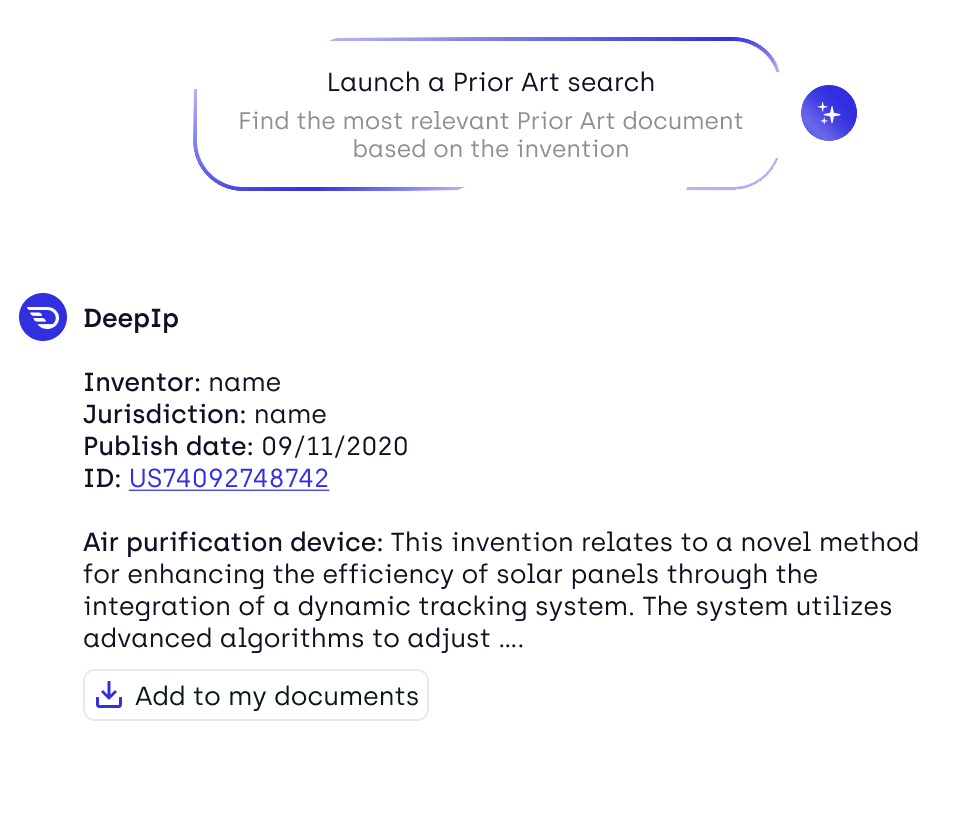

- Domain-specific technical refresh cycles, especially in AI hardware, ML accelerators, and quantum logic

- Live tracking of examiner behavior across relevant art units, to anticipate how unfamiliar technologies will be handled

- Analytics on office-action patterns in emerging domains to detect new rejection trends early

- Automated comparison tools to prevent drift across related filings as the underlying tech evolves

This is where Capron’s two identities—former examiner and high-volume prosecutor—click together. Examiner-minded drafting provides the structure; modern legal-tech provides the scale.

And the teams that master both will be the ones drafting patents for technologies the USPTO hasn’t even categorized yet.

The Examiner’s Perspective Is Becoming Essential Again

Capron’s reflections reveal a truth that modern patent prosecution is circling back to: adopting an examiner’s perspective—across classification strategy, AI-era drafting, and portfolio consistency—is now essential.

The attorneys who will lead the next decade of innovation are those who:

- Draft with an examiner’s logic

- Anticipate classification outcomes

- Maintain consistency across massive portfolios

- Adopt technology with rigor rather than churn

- Build workflows that keep them current in technical domains that never slow down

In a field defined by rapid invention and increasing complexity, these habits form the foundation of high-quality, future-ready patent prosecution.

.png)